Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

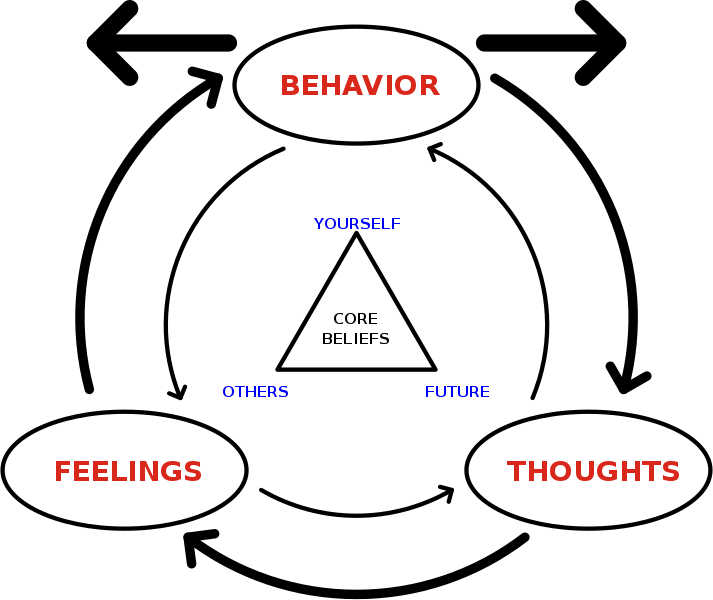

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) combines behavioral modification therapy techniques with and cognitive therapy. The basic idea of the ‘cognitive’ element of CBT is that our thoughts influence how we feel, and how we behave (see the diagram below). CBT approaches distorted thinking as a source of distress which can be treated with the help of a therapist. A distorted thought is one that does is not reflective of reality. Furthermore, the perspective of cognitive behavioral therapy is that certain situations, in and of themselves, do not cause particular feelings and reactions. Rather, it is the meaning we attribute to those situations that causes our feelings and reactions.

Example of Distorted Thought

Situation: While I am out doing errands, my friend walks right past me on the street without acknowledging me.

Thoughts: “Did I do something wrong?” “I can’t imagine why he didn’t notice me.”

Feelings: I was confused, sad, and hurt.

Behavior: I stood there on the sidewalk for a few seconds, before finishing my errands and going home. Later, I call my friend to see what was up.

On the call, my friend tells me that at that time, he had just heard that his mother was in a car accident and she was in the hospital. He said he was a nervous wreck and almost completely preoccupied until he found out that she was alright.

It is not unusual for us to feel hurt if a friend does not greet us. But if we have a consistent pattern of distorted thinking, to the degree that it begins to affect the quality of our life, it can be a problem.

CBT Treatment for OCD and Anxiety

CBT is empirically supported for the treatment of the full range of anxiety disorders, including obsessive-compulsive disorder, depressive disorders, personality disorders, substance abuse, and tic disorders. Cognitive behavioral therapy is designed to be a time-limited, outcome-focused treatment which provides the means to improve your life by learning to correct distorted thinking. Treatment with CBT will provide you with the skills to examine your beliefs about the world, your view of yourself, and the relationship between the two.

Contact Harold Kirby at 610-517-3127 to schedule a consultation or appointment for CBT treatment. Harold provides telehealth treatment for clients in Philadelphia and the surrounding areas of Pennsylvania and New Jersey (Main Line, Montgomery County, Camden, Cherry Hill), as well as in the South Carolina Lowcountry (Hilton Head, Bluffton, Beaufort, Colleston County, Dorchester County, Berkeley County, Charleston).

Read through the descriptions of common cognitive distortions below to get a clearer understanding of the patterns of distorted thinking that CBT may help address.

15 Common Cognitive Distortions

By John M. Grohol, Psy.D.

Aaron Beck first proposed the theory behind cognitive distortions, and David Burns was responsible for popularizing it, using common descriptions and examples for the distortions.

1. Filtering or Selective Abstraction

Through filtering abstraction, individuals take negative details of a circumstance and magnify them while ignoring any and all positive aspects of a situation. For instance, a person may pick out a single, unpleasant detail and dwell on it exclusively so that their vision of reality becomes darkened or distorted.

2. Polarized Thinking (a.k.a “black and white” or “all-or-nothing” thinking)

In polarized thinking, things are either black or white, without any gray area. We are perfect or we are a failure; there is no middle ground. People or situations are placed into “either/or” categories, with no allowances for the complexity inherent in people and situations.

3. Overgeneralization

By overgeneralizing, we arrive at a general conclusion based on a single incident or piece of evidence. If something bad happens once, we expect it to happen over and over again. A person may see a single, unpleasant event as part of a never-ending pattern of defeat.

4. Jumping to Conclusions

When we jump to conclusions we assume that we know what another person is feeling and why they are behaving a certain way, without that person saying so. In particular, we assume that we are able to determine how people are feeling toward us. For example: a person may conclude that another person is reacting negatively toward, but doesn’t bother to actually determine whether or not that is the case. Or, a person may anticipate that a situation will turn out badly, and will convince themselves that their prediction is a foregone conclusion.

5. Catastrophizing (a.k.a. “magnifying” or “minimizing”)

When we catastrophize, we expect disaster to strike. We hear about a problem and use what-if questions (e.g., “What if tragedy strikes?” “What if it happens to me?”). For example: a person might exaggerate the importance of insignificant events (such as their own mistake, or someone else’s achievement). Or a person may inappropriately diminish the meaningfulness of an event or quality, thus minimizing it to the point of insignificance (e.g., a person’s own desirable qualities, or someone else’s imperfections).

6. Personalization

Personalization is a distortion where an individual believes that the actions and behaviors of others are a direct, personal reaction to the individual. When we personalize, we also compare ourselves to others, trying to determine who is smarter, better-looking, etc. A person engaging in personalization may also see themselves as the cause of some unhealthy external event that, in reality, they were not responsible for. For example: “We were late to the dinner party, which caused the hostess to overcook the meal. If only I had pushed my husband to leave on time, then this wouldn’t have happened.”

7. Control Fallacies

The fallacy of external control causes us to see ourselves as helpless a victim of fate. For example: “I can’t help it if the quality of the work is poor, my boss demanded I work overtime on it.”

The fallacy of internal control causes us to assume responsibility for the pain and happiness of everyone around us. For example: “Why aren’t you happy? Is it because of something I did?”

8. Fairness Fallacy

The fallacy of fairness causes us to feel resentful because we think we know what is fair, but other people don’t agree with us. As many are told as we’re growing up and things don’t go our way: “Life isn’t always fair.” Those who go through life judging the fairness of every situation will often feel bad because of it, because life isn’t “fair” — things will not always work out in your favor, even when you think they should.

9. Blaming

When we blame, we hold other people totally responsible for our pain, or, conversely, blame ourselves for every problem. For example: “Stop making me feel bad about myself!” Nobody can “make” us feel any particular way—only we have control over our own emotions and emotional reactions.

10. ‘Shoulds’

When we think in terms of ‘shoulds’, We have a list of ironclad rules about how ourselves and others ought to behave. People who break the rules make us angry, and we feel guilty when we violate these rules. A person may often believe they are trying to motivate themselves through their shoulds and shouldn’ts. For example, “I really should exercise. I shouldn’t be so lazy.” Musts and oughts are also offenders. The emotional consequence is guilt. When a person directs ‘should’ statements toward others, they often feel anger, frustration, and resentment.

11. Emotional Reasoning

When we use emotional reasoning, we believe that what we feel must be true. If we feel stupid and boring, then we must be stupid and boring. We assume that our unhealthy emotions reflect the way things really are.

12. Fallacy of Change

We expect that other people will change to suit us if we pressure or cajole them enough. When our hopes for happiness seem to depend entirely on other people, we feel the need to change them.

13. Global Labeling

Global labeling involves generalizing one or two qualities of ourselves or others into an extreme, global (total) judgment. Instead of describing an error in the context of a specific situation, a person attaches an unhealthy label to themselves. For example: after failing at a specific task, a global labeler may say “I’m a loser.” When someone else rubs them the wrong way, a global labeler may say “He’s a real jerk.” Mislabeling involves describing an event with language that is highly colored and emotionally loaded.

14. Always Being Right

Those who must always be right are continually on trial to prove that their opinions and actions are correct. Being wrong is unthinkable, and they will go to any length to demonstrate their rightness. Often, being right is more important than the feelings of others, even loved ones. For example: “I don’t care how badly arguing with me makes you feel, I’m going to win this argument no matter what because I’m right.”

15. Heaven’s Reward Fallacy

We expect our sacrifice and self-denial to pay off, as if someone is keeping score. We feel bitter when the reward doesn’t come.

Source: https://psychcentral.com/lib/15-common-cognitive-distortions/0002153

References:

- Beck, A. T. (1976). Cognitive therapies and emotional disorders. New York: New American Library.

- Burns, D. D. (1980). Feeling good: The new mood therapy. New York: New American Library.

This Post Has One Comment

Comments are closed.

Pingback: Anxiety treatment centers- What to expect